After publishing his 2019 bestseller, The Color of Compromise: The Truth about the American Church’s Complicity in Racism, the question Jemar Tisby says he kept getting was, “So, what do we do about it?” Which Tisby takes to be a recognition of the “fierce urgency of now.” It, of course, is what the subtitle of Color of Compromise indicates: the American church’s alleged acquiescence to racism past and present. In Tisby’s words,

“[A]fter more than three centuries of deliberate, systematic race-based exclusion, the political system that had intentionally disenfranchised black people continues to do so, yet in less overt ways. Simply by allowing the political system to work as it was designed –to grant advantages to white people and to put people of color at various disadvantages– many well-meaning Christians were complicit in racism.” [p. 171].

It was (and is) Tisby’s contention that “racism changes over time… racism never goes away; it just adapts.” Hence, even contemporary Christians, though they do not support chattel slavery or Jim Crow segregation, remain complicit:

“Christian complicity with racism in the twenty-first century looks different than complicity with racism in the past. It looks like Christians responding to black lives matter with the phrase all lives matter. It looks like Christians consistently supporting a president whose racism has been on display for decades. It looks like Christians telling black people and their allies that their attempts to bring up racial concerns are ‘divisive.’ It looks like conversations on race that focus on individual relationships and are unwilling to discuss systemic solutions. Perhaps Christian complicity in racism has not changed much after all.” [p. 191].

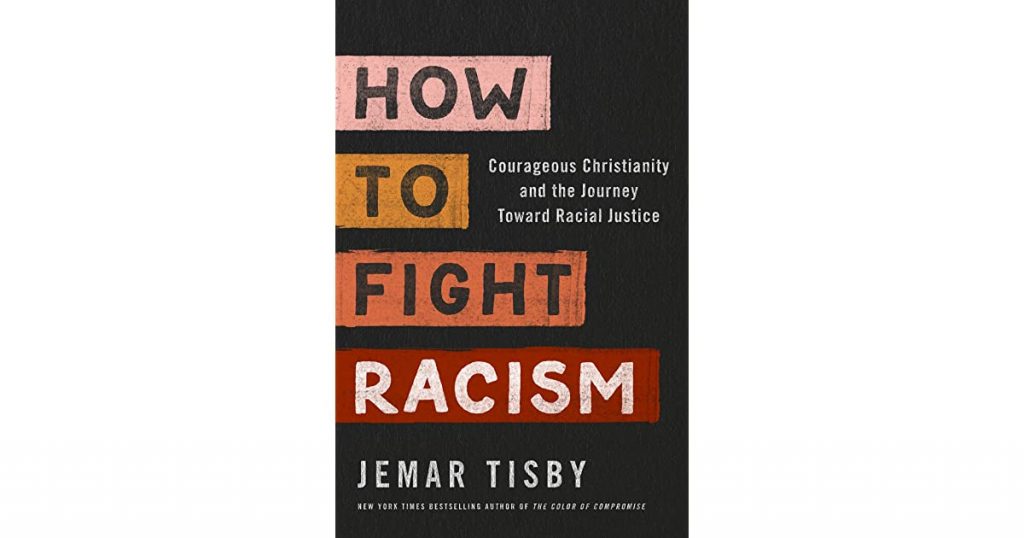

Though the latter part of Color of Compromise was taken up, in part, with some policy analysis and proposals, it presented no clear action plan. If Tisby’s assessment was true, what was the church to do? In his latest book, How to Fight Racism: Courageous Christianity and the Journey toward Racial Justice, Tisby picks up where he left off—a sort of extension of the last few chapters of Color of Compromise—capitalizing on the narrative and assumptions established in his previous work. Indeed, the two seem to be meant to be read in tandem.

Defining “Racism”

HTFR is divided into three parts: Awareness (understanding), Relationships (partnerships), and Commitment (action)—corresponding to Tisby’s “ARC” approach to “racial justice”—each comprised of three manageable chapters, with “Essential Understandings” and “Racial Justice Practices” therein. Combined with the standalone opening chapter, the first section (“Awareness”) is, generally, occupied with providing both definitional and conceptual fundamentals along with some advice on how the reader can bolster their understanding of the same.

For any book, any argument, the definitional work at the start is important. It informs the subsequent polemic. Already, at the very outset of HTFR, we encounter problems, at least for the Christian reader. Namely, that Tisby clearly relies on definitions and concepts drawn from Critical Race Theory (CRT) to set the stage and inform his argument, as we shall see.

“Racism,” Tisby says, is “a system of oppression based on race” and is “a problem nationwide and worldwide.” (p. 4). “Racism uses an array of tactics to deceive, denigrate, and dehumanize others.” (p. 5). What’s more, “everyone is either fighting racism or supporting it, whether actively or passively.” (p. 4). Here we see the influence of cutting edge, popular level race scholarship. Namely, that of Ibram X. Kendi, the author of How to Be an Antiracist, which Tisby cites approvingly in HTFR (p. 157). (It was recently announced that Tisby will be joining Kendi’s Antiracism Center at Boston University as the Assistant Director of Narrative and Advocacy.) Kendi’s now (in)famous definition of “antiracism” features a similar extremism of which Tisby’s comments on racism are derivative:

“The opposite of ‘racist’ isn’t ‘not racist.’ It is ‘anti-racist’… One either allows racial inequities to persevere, as a racist, or confronts racial inequities, as an antiracist. There is no in-between safe space of ‘not racist’… The claim of ‘not racist’ neutrality is a mask for racism.”

Moving beyond the “binary of racist and not racist” is key, Tisby explains, because “everyone may act in ways that support racism at times,” but especially for white people who “support the racist status quo by choosing comfort and privilege.” (p. 8). Hence, whilst Tisby recognizes that people of color have the capacity for prejudice, HTFR is meant to “pertain especially to white people because white people bear the most responsibility for racism.” (p. 11), a charge that is maintained throughout the book.

Though Tisby claims that he does not intend to “pit the personal against the systemic,” the lion’s share of his treatment of racism follows the trend of the day in that it heavily emphasizes the systemic and the way that racism, as institutionalized, continues to change forms (p. 31). Indeed, Tisby acknowledges that, in recent years, his focus has shifted from “increasing interracial understanding through relationships to working for systemic and institutional change.” (p. 156). As it pertains to HTFR, the “Commitment” to “dismantle racist structures, laws, and policies” to “enact society-wide change” overshadows and somewhat undermines any talk of personal change that occurs through “friendships and collegiality” (p. 5). This skewed approach, despite the author’s assurances to the contrary, is informed by his understanding of racism as, first and foremost, a system of oppression, that is, as prejudice plus power.

“[R]acism is more than an individual or interpersonal attitude,” writes Tisby. “It includes systems, structures, and institutions owned and operated by those who hold the power to make decisions.” (p. 49). He then quotes Renni Eddo-Lodge’s bestselling, Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race:

“Everyone has the capacity to be nasty to other people, to judge them before they get to know them. But there simply aren’t enough black people in positions of power to enact racism against white people on the kind of grand scale it currently operates against black people.”

Hence, “[F]ighting racism necessitates working for change beyond an interpersonal level; substantive change requires shifts at the institutional and policy level too.” (p. 156). This is also why reverse racism is an “erroneous concept.” (p. 49). “Our society has been deliberately constructed to keep white people segregated from people of color.” (p. 110). But, in a veiled nod to intersectionality, Tisby holds that our white dominated society does not only oppress people of color because “Race intertwines with sex and class in a sticky web of exploitation and oppression.” (p. 20). He later clarifies that “[C]onfronting the interlocking pattern of practices and policies that create and maintain racial inequality is what love looks like in public.” (p. 180).

Accordingly, Tisby implores readers, as a condition of racial “awareness and maturity,” to “develop” their racial identity (which is “not static”)—via “color-consciousness,” and over and against colorblindness—within a presumably “race-conscious society.” (p. 41). This exercise is meant to uncover the “social meaning” of one’s identity and, in the case of whites, produce recognition of “unearned advantages in a society that favors whiteness.” (p. 48). Ultimate racial maturity manifests in white people as allyship and advocacy. (p. 50). Expressions of allyship and advocacy presented in the first few chapters include talking to kids about race and funding “therapists of color” to confront racial trauma. Most importantly, however, it involves (for white people) listening to people of color who possess an “indispensable experiential knowledge about the ways racism functions.” (p. 64).

Defining “Racial Justice”

Perhaps the most frustrating feature of HTFR is that whilst encouraging readers to embark on the “journey” of “racial justice” it never clearly defines the term. Rather, the idea must be pieced together along the way. The result is a hodgepodge of imperatives (and, later, policies), informed by Tisby’s definition of racism. “Racial justice” is characterized by “a commitment to dismantle racist structures, laws, and policies,” i.e., “those that have a disparate impact on people of different races.” (p. 5).

In the end, whether the author himself has a terse definition of “racial justice” in mind is anyone’s guess, but within the covers of HTFR “racial justice” seems to function as a convenient catchall for whatever policy the author favors (see below). Love or hate HTFR, this is a glaring shortcoming that hampers its case. Readers can decide for themselves whether this definitional conundrum is fatal to the book’s thesis and purpose, and whether it represents mere carelessness or strategic ambiguity.

What is clear is that “racial justice” is a “transformative,” all consuming “journey” (pp. 5, 89), a disposition to which all of life must be oriented (pp. 181-202). “Racial justice is a lifestyle not an agenda item.” (p. 182). “Fighting racism does not consist of a set of isolated actions that you take; rather these actions must flow from an entire disposition that is oriented toward racial justice.” (p. 181). This entails repositioning yourself “spiritually, emotionally, culturally, intellectually, and politically.” (pp. 181-182).

The lifestyle of racial justice requires a “daily compact with yourself and others… It is a commitment to living in such a way that your entire life is a witness for racial justice.” (p. 182). “It is about being a good ancestor.” (p. 182). To his credit, Tisby does instruct racial justice warriors to put away contempt for those less woke than themselves (pp. 182-183). But there is no question of who is right. The racial justice warrior is, he just needs to be humble about it. “In our journey toward racial justice, we must always self-monitor for the ways we are reenacting racism, even if unintentionally, and see to correct our attitudes and behaviors.” (p. 184).

The racial justice lifestyle—taking up your racist cross daily—sounds a lot like any discipleship plan. Stay humble. Work with others. Do not rely on willpower alone, etc. The goal is to “orient your entire life around racial justice” (p. 186) and to “hone your racial reflexes so you can respond nimbly and adeptly to the various ways you will continue to encounter injustice.” (p. 186). The perpetual path of racial justice necessitates repeated reflection, contemplation, and confession—something like reflexivity and positionality—especially for white people.

Because of their privilege and blindness (both willful and passive), “White people must constantly cultivate humility in order to acknowledge their complicity in racism and engage in the process of repentance and repair.” They must “go through a process of deconstructing the ways white supremacy has skewed your perception in order to see the reality of race more clearly.” (pp. 184-185).

Within this context, HTFR also introduces a relationship of antagonism between “racial justice” seekers and “racial justice resisters.” The latter are those that “remain steadfastly committed to denying the present reality of racism and not doing much to curb it.” (p. 115). These are people who opt for only “vague” condemnations of racism and proclamations of equality. (p. 103). They also insist that racism is “a matter of individual actions,” that is, they deny that racism is endemic to society, culturally normative, and structurally reinforced (pp. 91-92, 95).

Resisters will not embrace the lifestyle and are living impediments to “racial progress.” This setup seems to be standard operating procedure for Tisby. A similar dichotomy was established early on in Color of Compromise between those who work for justice and those who “deny or defend racism.” Thankfully, Tisby does stop shy of condemning these detractors as out-and-out racists themselves, but at certain points it is almost implied. This artificial antagonism conjured up by Tisby counteracts his commendable comments on the indispensability of genuine friendships to racial reconciliation, or the “spiritual dimensions of race relations.” (pp. 87-88).

Pursuing “Racial Justice”

Each chapter of HTFR features an application section—the latter third is dedicated to “Commitment,” by which Tisby means application and action—which instructs the reader on the pursuit of “racial justice.” For example, in a chapter on “How to Study the History of Race,” Tisby advises that “Racial justice requires removing monuments that honor racist individuals and white supremacy.” (p. 74). To be fair, it is often in the application sections of each chapter that HTFR features useful and thought-provoking insights. In discussing Confederate monuments, for instance, Tisby makes a distinction between “veneration and remembrance,” noting that the past should always be remembered, “even the most painful parts,” but that not all figures and events deserve veneration. This is a good distinction that could contribute to these sorts of conversations. Yet, such moments of sobriety and nuance are the exception in HTFR.

Rather than simply advocating for the insertion of this distinction into the discussion, Tisby declares that a “minimum requirement for racial progress” is the removal of “statues and symbols of racism.” (p. 76). No clarifying examples are given, which effectively absolutizes the principle but leaves it without an arbiter of its application.

Does Tisby have James P. Boyce in mind? San Francisco schools, whilst citing the Declaration of Independence, recently removedThomas Jefferson’s name from those schoolhouses bearing it. Is this a nuanced application of Tisby’s distinction between remembrance and veneration? What about the great emancipator himself, Abraham Lincoln, who is now being subjected to the monument removal craze. Winston Churchill? Tisby makes no effort to wade into the complicated scenario to which his axiom allegedly applies.

Nevertheless, the wearisome way of the racial justice disciple entails action, and certain corresponding policy commitments too. Predictable prescriptions like fighting voter disenfranchisement, writing a small check to a black organization (like The Witness, let’s say (p. 172)), and advocating for reducing incarceration, are mentioned. Juneteenth should be celebrated, so long as it is not appropriated by white people, as an act of racial justice. (p. 81). Reparations should be paid to black people (p. 167). Colin Kaepernick and Stacey Abrams are featured as exemplars of “racial justice work.” (pp. 161, 193). So on and so forth. Many people may be in favor of some of these proposals. Christian groups like Prison Fellowship, for example, have been working to overhaul the prison system for decades; noble and much needed work, to be sure.

In Tisby’s world, however, each of these things is supplied with a racial justice impetus and end; disparities are both the cause and evidence of racism. We must abolish the death penalty because “victims of the death penalty are disproportionately Black.” (pp. 175-176). A shout out to the #DefundthePolice movement is also given (pp. 177-178), citing both Mariam Kaba’s New York Timesarticle and Angela Davis’ call for abolishing police. This racial impetus appears to be what distinguishes one action over another as “racial justice.”

Most of all, racial justice pursuers must fight systemic racism, everywhere. That is, they must work to “eliminate disparities in racial economic well-being, security, and opportunity.” (p. 159). One way to do this, advises Tisby—and one gets the impression that it is the only way—is to “think about the effect of policies.” For this approach, Tisby quotes his new colleague, Ibram Kendi, who explains that “any measure that produces or sustains racial inequality between racial groups” is, in fact, a racist policy. “There is no such thing as a race-neutral policy,” says Tisby. Rather, (quoting Kendi, again) every policy is “producing or sustaining either racial inequity or equity between racial groups.” In this outcome-based policy analysis, adds Tisby, impact is more important than intent. “We must look at outcomes to evaluate whether a policy moves us further toward racial justice or further from it.” (p. 160).

At this point, it appears that “equity” and “racial justice” have become synonymous. In the first chapter, Tisby notes that “equity” differs from “equality,” in part, because it “accounts for identities (race, ethnicity, ability, nationality, gender, etc.) and circumstances that may otherwise hinder the success of one participant over another.” (p. 4). What is clearer is that Tisby’s “racial justice” possesses a strong, self-conscious affinity with Kendi’s “antiracism.”

Corporate Repentance

Tisby’s operative definition of racism has other, sometimes faulty, implications for his “racial justice practices” as applied to churches. Some of this advice is relatively innocuous if seemingly random, like doing a group study on race (p. 125). Others are more controversial, like race-based redistribution of church funds (p. 147). Others still are quite a bit more than controversial. A representative example will suffice: corporate repentance.

Tisby advises corporate confession of racism in churches over and against the refrains of “racial justice resisters,” those who question a race-based collective or imputed guilt. “Racial justice resisters will argue that no one can be expected to repent of racist acts they did not personally commit,” he says. “But their argument fails based on what the Bible teaches about confession.” (p. 95). Tisby’s prooftext is Ezra 9:6-7, an oft cited passage for those of Tisby’s persuasion, and, indeed, it does possess some relevance to the inquiry, but, on close examination, it is his argument that falls flat.

As readers may recall, following the reconstruction of the temple in Jerusalem per the leniency of King Cyrus, the prophet Ezra implored God for forgiveness on behalf of the people’s sin which had infected their covenant community for some two generations. “From the days of our fathers until now, our guilt has been great,” cries out the prophet. (Ezra 9:7). Tisby sees this passage as a justification of his call for corporate confession of every church on the path of racial justice (p. 96).

Tisby assumes a racist past of at least most churches. “Any church, especially those that have been in existence for a long time, should engage in a process of uncovering and confessing their racial history.”(p. 98) Tisby also states earlier that “We are all implicated in injustice” (p. 73) because “most people in North America benefit from the theft of Native land.” White people, in particular, must “remember their historic role in racial injustice,” which should be cause for “humble contrition.” (p. 81).

Given Tisby’s conception of racism discussed above, white churches, one way or another, are necessarily partakers of whiteness, socio-cultural capital generated by their systemic privilege within a white dominant society. Though Tisby instructs churches to dig into the past of their respective congregation to unearth any racist conditions of their history, this exercise seems somewhat superfluous. If predominantly white churches—indeed, all Americans—are already “implicated in injustice” then inquiring as to whether a church was (actually) founded for, by, or through racism is of little consequence. We already know the answer.

Tisby takes the example of Ezra to mean that everyone within the white church has “a responsibility to examine the boundaries of their bigotry.” Again, the presence of bigotry is assumed as a matter of course. “What has your community tolerated when it comes to racism? What has it permitted as far as prejudice? What has your community determined to be the acceptable pace of change?” (p. 96).

All of this is not far off from Robin DiAngelo’s (in)famous instructions. DiAngelo—White Fragility is cited approvingly in HTFR (p. 48)—assumes that all white people are complicit in racism, and, indeed, racist. Accordingly, the question is not whether a given situation was racist, but rather how racism manifested in that situation. Similar logic is active in HTFR, though bolstered by error-laden exposition of the prophets.

Returning to Ezra, to see where Tisby has erred we must understand the passage in terms of the covenantal community of which Ezra was a part. First, it helps if the pericope in focus is set within the context of the passage and subsequent passages, which HTFR does not do, extracting only versus six and seven instead, which fit the author’s narrative but not that of Ezra itself.

National Covenant

Certainly, in our own time, our congregations continue to fill the role of covenantal community as Israel did. But the scope is distinct. Our church covenants do not include the nation—were it otherwise, it would certainly qualify as something like the “Christian Nationalism” so decried lately. Israel’s covenant, in terms of its subjects and substance, encompassed everything. (If Tisby wants an example of modern Christians doing something similar he need look no further than the New England Puritans which he vehemently denounces in chapter nine.) The church in America—assuming that speaking of it collectively and singularly is appropriate, which is not at all apparent—has never experienced that kind of socio-political organization. Congregational covenants are just that, congregational, even if they in some sense extend denominationally.

Therefore, it follows that churches can only implicated in racism, or any collective sin for that matter, if 1) the particular church is actually and demonstrably guilty of such, or 2) if, by way of being white, is attached to the alleged racism of all whites who profit from, and fail to resist, the privilege afforded to them by the white hegemony.

The point is, either a voluntary and valid church covenant is the operative connector or the (politicized) color of one’s skin is—the latter attaching any church anywhere in America to the sins of whites writ large in the past, present, and future regardless of their own individual actions and beliefs. The two options, within Tisby’s paradigm, are either an explicit church covenant or an implied racial one.

In principle, the first is an unobjectionable means of implication so long as the church in question is actually guilty of racism. The second means of implication is, well, rather racist and unbiblical. The first means of connection, the sin must still be proven. It is not enough for the members of a church to simply benefit from the racialized status quo, one which none of them contributed to constructing, which says nothing of the matter of whether such a conception of American society is reasonable. I digress.

“Since the days of our fathers”

Second, and more importantly, we must examine the passage involved. Tisby claims that, at the time of Ezra’s lament, the sins in question, disobedience and idolatry, were no longer active in the community. He writes, “[A]ll of this happened centuries before Ezra’s prophetic leadership of the Jewish people. So why is he confessing to God the sin of a previous generation?” (96).

On a plain reading of the text, this is evidently not the case. The princes come to Ezra and tell him that,

“The people of Israel and the priests and the Levites have not separated themselves from the peoples of the lands with their abominations, from the Canaanites, the Hittites, the Perizzites, the Jebusites, the Ammonites, the Moabites, the Egyptians, and the Amorites. For they have taken some of their daughters to be wives for themselves and for their sons.”

This is a present, ongoing sin that is plaguing Israel. Ezra had come to instruct them in the law and ordinances of God and finds out that the people were subverting it in the most fundamental way. As Matthew Henry put it, “They profaned the crown of their peculiarity.”

It may be assumed that the particular princes who informed Ezra of this travesty were not themselves engaging in such acts, but certainly some rulers were, as were the priests and the Levites, and the whole people, or at least a critical mass thereof. Top to bottom rank idolatry in violation of the covenant. Shechaniah, the son of Jehiel, confesses to this sin directly (10:2). Certainly, this practice was not of recent vintage, as 9:7 makes clear. It had been going on “since the days of our fathers.” It was not a novelty; the people were without excuse.

But it also had not ceased. If anything, it had gotten worse. Ezra makes this clear in 10:10-11 when he condemns the people for taking “strange” or pagan wives and thereby increasing “the trespass of Israel”—a better translation might be “adding to the guilt.” They are then instructed to make confession not on behalf of their forefathers, but for themselves to Yahweh, the God of their forefathers, and then to “separate yourselves from the people of the land.” A couple of verses later (10:13), the gathered assembly admitted that “there are many of us who have transgressed in this matter.” The judicial proceedings on the issue could not be completed in less than three days, so many offenders were present. They then all agreed (10:14),

“Let our officials stand for the whole assembly. Let all in our cities who have taken foreign wives come at appointed times, and with them the elders and judges of every city, until the fierce wrath of our God over this matter is turned away from us.”

By this, the Israelites hoped to “turn the fierce wrath of our God from us.” The rest of the chapter (vv. 18-44) simply lists all the guilty parties. The guilty sons of the priests repented and offered a sacrifice for their own guilt (10:18-19). Tisby’s attempt to leverage Ezra 9 to justify mandated corporate repentance for all white churches, therefore, falls flat. Were the sin Ezra condemned merely past, it would have been lamentable, but because it was also present it was also confessable. That being said, there are instructive corporate elements to repentance present in the passage. But they don’t aid Tisby’s cause.

None of this is to per se deny that there are churches today, whilst doubtless the minority thereof, who are guilty of congregation-wide racism, past and present. It is the job of their elders to lead them to swift confession, repentance, and correction, as Ezra did. As the leader of a covenant community, the pastor, even if he is not guilty of racism himself, must, in a way, take on the sin himself, confessing it for and with the people. To quote Henry again on Ezra,

“His address is a penitent confession of sin, not his own (from a conscience burdened with its own guilt and apprehensive of his own danger), but the sin of his people, from a gracious concern for the honour [sic] of God and the welfare of Israel.”

And for the rest of us, “the sins of others should be our sorrow,” added Henry. Even those we are not guilty of and, therefore, do not owe repentance for, should grieve us when they dishonor the name of God and that of his church. None of this conceptual and exegetical nuance is appreciated by Tisby in his cherry-picking of Bible verses to justify mandatory repentance for white churches—churches that, in his estimation, have been “white too long.”

Conclusion

As I have noted elsewhere, these same types of errors are repeated in his brisk and sloppy discussions of constitutional litigation surrounding the Voting Rights Act, the debate on reparations, and past historical figures. All of these are complicated, multilayered topics that no author could be expected to exhaust, especially in a popular-level book. But Tisby barely tries. Instead, each rather contentious subject is leveraged to suit the narrative of HTFR, which is determined at the outset. In this way, HTFR is a decidedly activist book, which seems intended by the author, though he is regularly presented in public as a trustworthy historian and nuanced theologian.

The root problem is that Tisby’s activist aims are informed by an artificial narrative built upon rather lax historical, exegetical, and analytical work. Unfortunately, this easily demonstrable character of the book overshadows any redeeming qualities therein. This in addition to his reliance on questionable source material for his definitional and conceptual underpinnings. His assumptions regarding “race,” “racism,” and “racial justice,” are never sufficiently demonstrated but inform the sophomoric analysis that occurs later in the book. Indeed, the latter is fitted to the former. In other words, from the word “go,” Tisby already knows what he is looking for. Everything else is a matter of convenience and convention.

Despite flashes of beneficial commentary, HTFR is unhelpful and frustrating, and delivers more confusion than clarity. Its narrative-driven, weak analysis infects even the otherwise balanced insights with bias. Its mishandling of Scripture and, at times, the historical record—something present in his first book as well—induces a distrust in the reader that is difficult to shake off. (Neil Shenvi has demonstrated similar problems in Ibram X. Kendi’s bestseller, Stamped from the Beginning.) This is never good for a book, nor is it good for the church.

Worse still, the asymmetry set up between whites and blacks via his definition of racism, and the fundamental antagonism established between racial justice pursuers and resisters, threaten to sow division rather than unity and reconciliation in the church. HTFR, therefore, cannot be recommended for carefully and faithfully addressing the problem it purports to address.